5 Things Formula 1 Racecars and Military Fighter Jets Have In Common

When it comes to speed, noise and the uncanny ability to make you stop what you’re doing and gawk, two mighty machines stand out: Formula 1 racecars and military fighter aircraft. Despite their distinct domains, these high-performance vehicles share surprising similarities—both in the machinery themselves as well as the drivers and pilots who operate these engineering marvels.

Without further ado, lights out and away we go…

1. The Noise

When people think of fighter jets, they usually think of the mighty roar and deep rumble that is heard long before the aircraft is ever seen. And although it’s not well portrayed when watching through a television, Formula 1 cars are also renowned for their ability to displace airwaves with force.

Although the engines are completely different, both fighter aircraft and Formula 1 cars are able to produce over 130 decibels. To put that in perspective, a live rock concert would be somewhere around 100 dB. Except for a Nickelback concert, of course, which produces 0 dB because if a tree falls in the woods… yeah, no one sticks around for Nickelback concerts.

Fun fact: racecar drivers and fighter pilots alike wear the same kind of custom-molded ear protection with speakers built into their ear canal so they can communicate with their teams.

2. The Wings

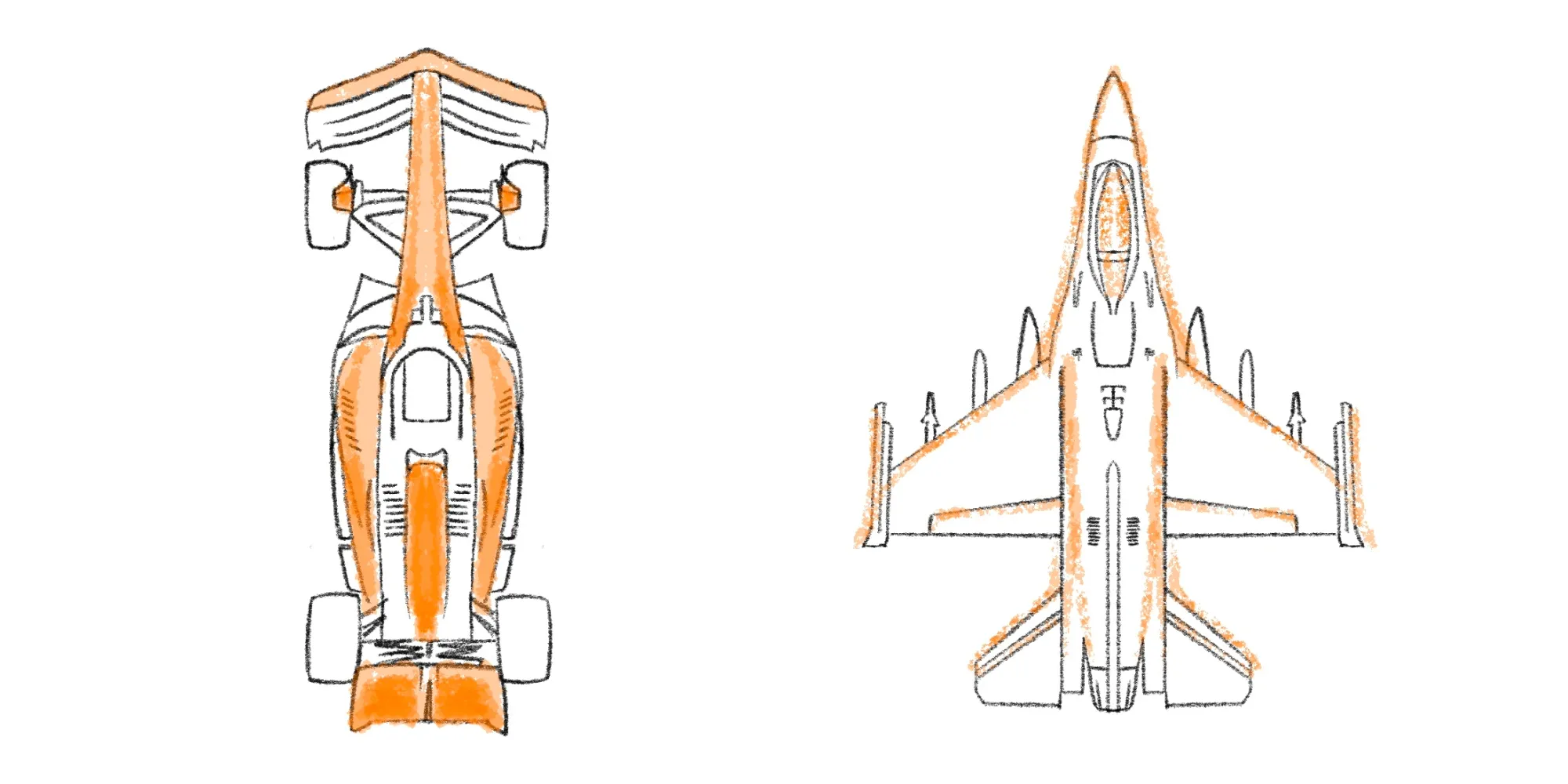

Although Red Bull is one of the biggest sponsors in Formula 1, that’s not the reason their cars have wings. And although both aircraft and racecars utilize wings for aerodynamic gain, they’re used in almost opposite ways.

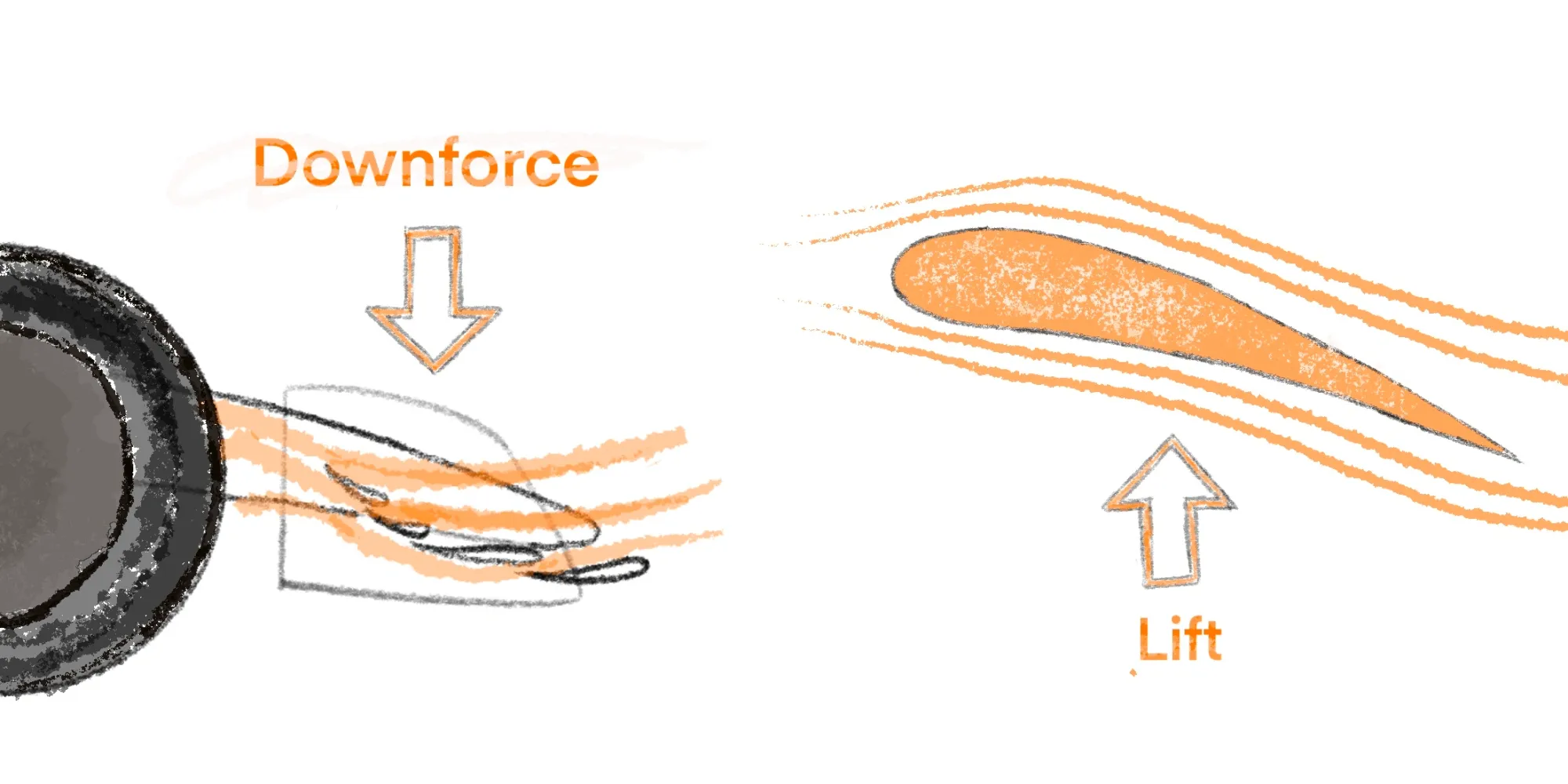

Airplanes use wings for lift—an upward force that counteracts the effects of gravity allowing a pilot to fly high into the air. Formula 1 cars, on the other hand, use wings to increase downforce—the opposite of lift.

But why?

Fighter jets and Formula 1 cars both are built for speed but fighters have the unique ability to be able to bank their wings in a turn and change their direction on a dime. Most race tracks, however, aren’t banked which can cause cars to slip out due to the centrifugal force experienced during a turn. This is why racecars use wings to turn airflow into downforce, practically gluing the cars to the track and increasing a driver’s ability to take a car at high speeds.

3. The Cost

The teams of people and resources required to ensure a Formula 1 car is ready on race day or for a fighter jet to blast off from an aircraft carrier come at no small cost. A 2023 Formula 1 car is estimated to cost around $16 million dollars while an F-16 fighter jet is estimated between $12 and $35 million, depending on the configuration.

On an annual basis, Formula 1 teams are allowed to spend up to (and sometimes over cough Red Bull cough) $145 million per year. In a not-so-similar comparison, the US Air Force has an annual budget of $215 billion.

HOWEVER. The US Air Force has 5,217 aircraft in its inventory while a Formula 1 team has 2 cars. So on a per-vehicle-cost, Formula 1 spends way more per racecar at $72.5 million whereas the Air Force is a mere $4.1 million.

Nothing about that cost comparison makes any actual sense and the only real conclusion to be drawn here is, why are awesome things always so expensive?

4. The Controls

No, I’m not saying flying a high-performance military-grade aircraft is anything like driving the fastest 4-wheeled vehicle on Earth but where they do, once again share similarities is in the controls.

See, now commonplace in all military jet aircraft are HOTAS controls—or Hands On Throttle-and-Stick. This is a fancy term for a system that places many common buttons and switches a pilot would need to manipulate the aircraft right on the stick and throttle, minimizing the time their hands are away from the two most important control devices. Most commonly on the stick and throttle are trim control, nose-wheel steering, speed brakes, and radio push-to-talk buttons among many other things.

Formula 1 drivers also have a steering wheel covered in buttons and switches for adjusting the performance of the car. What kind of resembles something made from Bop It, their steering wheels allow drivers to control things like gear shifting, engine torque, radio communication, and brake balance. They can even get a squirt of water into their mouth at the press of a button. Unless you’re Kimi.

5. Minimum Effective Safety

With both these engineering marvels built for pure performance, every gram of material and every inch of space matters, and nothing is added just for the hell of it. Certainly very little is added just for comfort, but the engineers that designed these monsters have done an incredible job at keeping drivers and pilots safe in the simplest, most effective ways possible.

Everyone is familiar with fighter jets and their use of ejection seats. A seat strapped to a rocket and a parachute save you from near death in less than a second. All you have to do is pull that handle between your legs and away you go. That really is it. No airbags, no seat cushions for floatation, just a canopy that blows up with explosive det cord and a ride on the ol’ Martin-Baker, accelerating at up to 20 times the force of gravity to let you live to fight another day.

Formula 1, one of the most dangerous sports in human history, has an ever-improving safety record. Unfortunately, a lot of the improvements made come at the cost of lessons learned from drivers who have crashed and lost their lives. Thankfully now Formula 1 utilizes a lot of safety standards such as the halo, gearbox-engine separation in the design of the cars, and g-force measuring in the drivers and car. These are all ways teams are able to balance maximum safety without taking away from the performance too much.

Now you know! Fighter jets and high-performance racecars share a lot of things in common. But what about their drivers/pilots? Stay tuned!